salcano

Solkan Railway Bridge

Gorazd HUMAR

HISTORY

THE WORLD’S LARGEST STONE ARCH BRIDGE

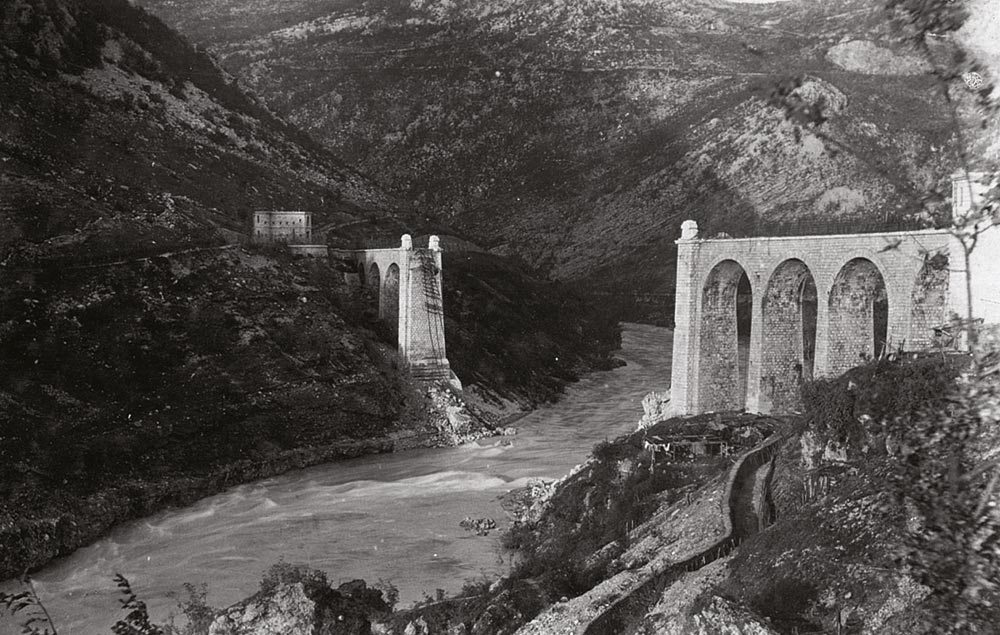

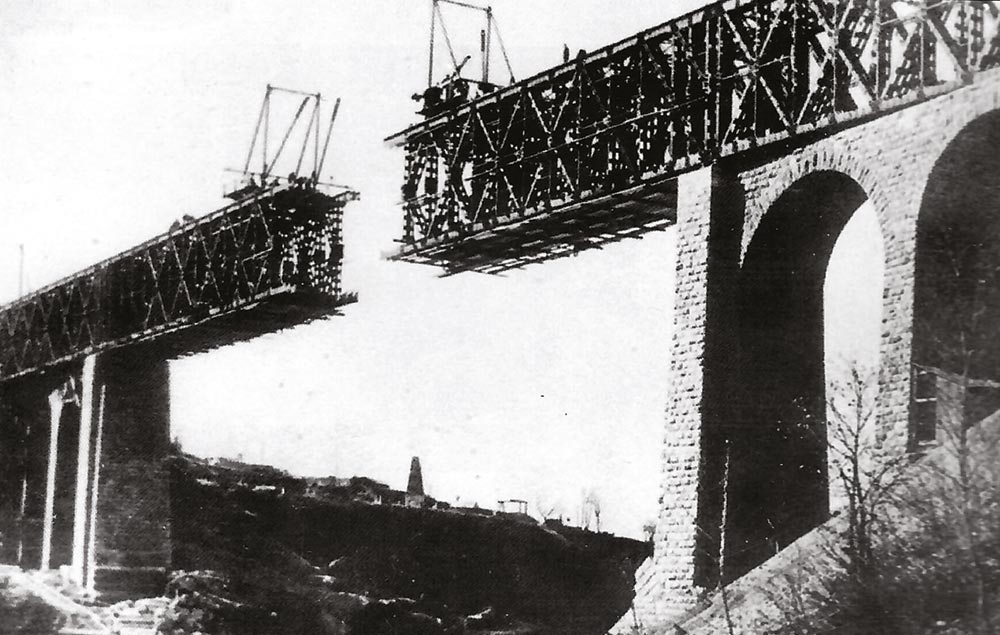

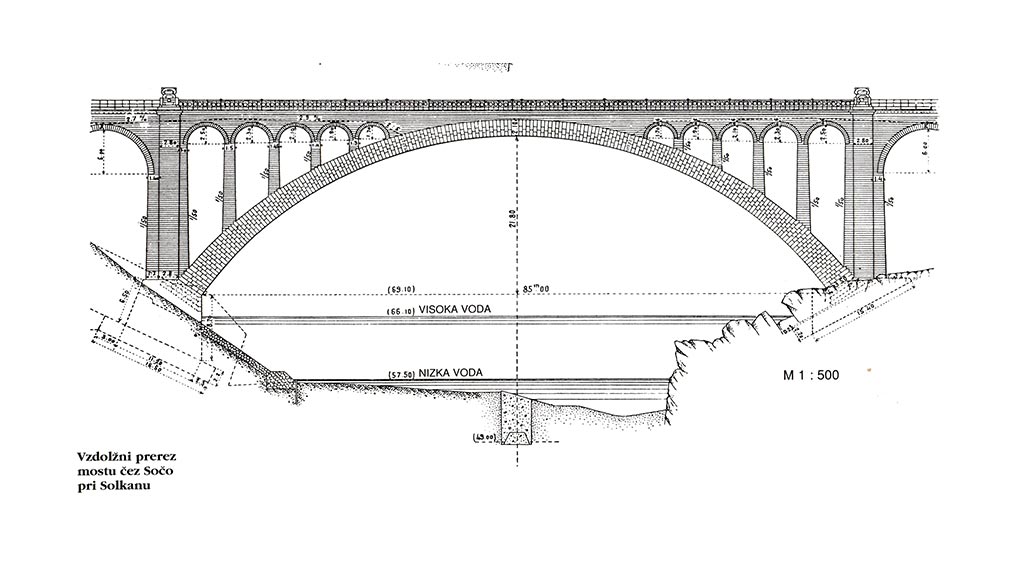

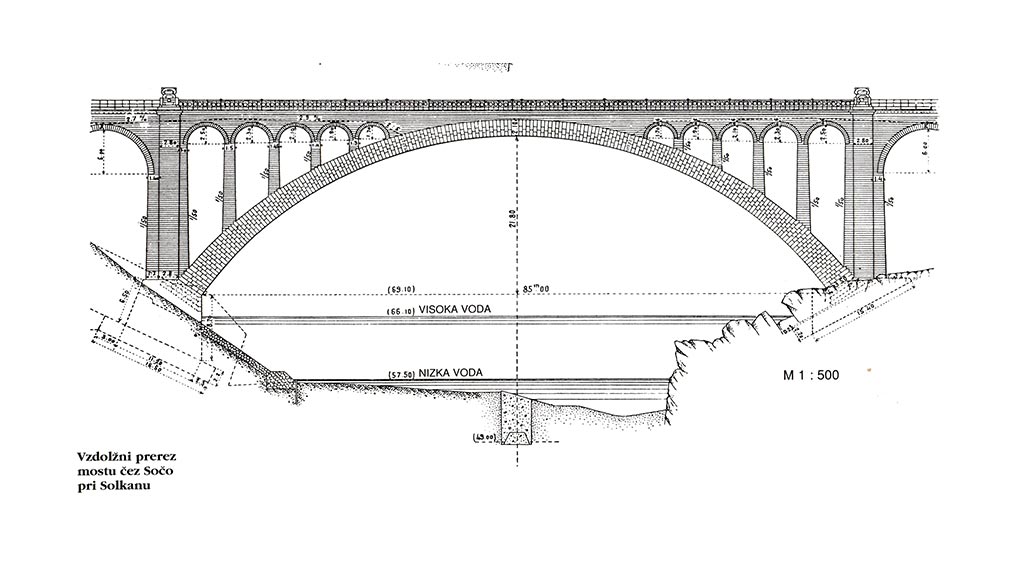

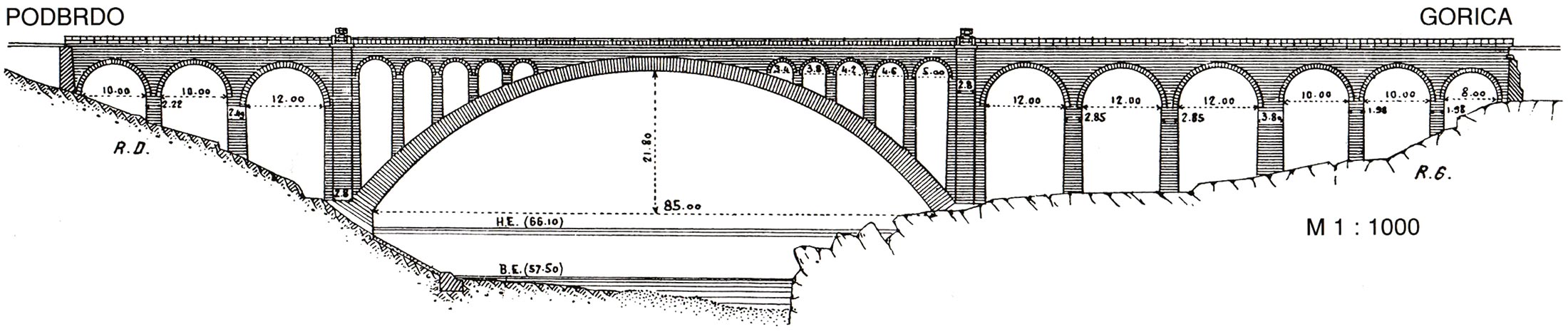

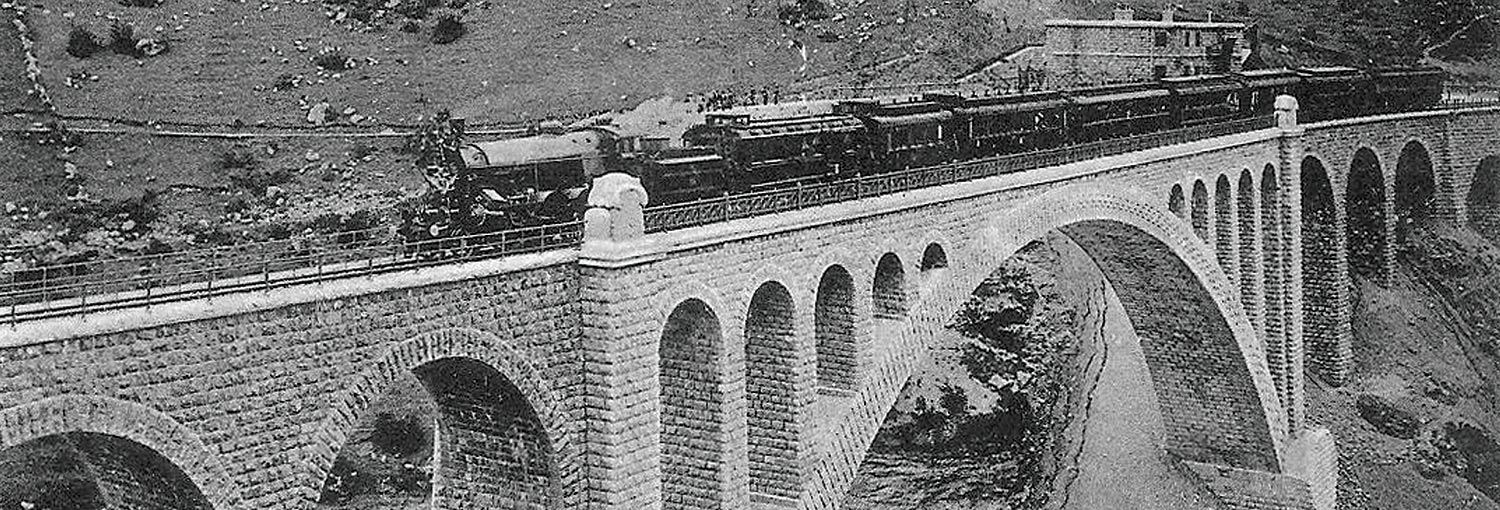

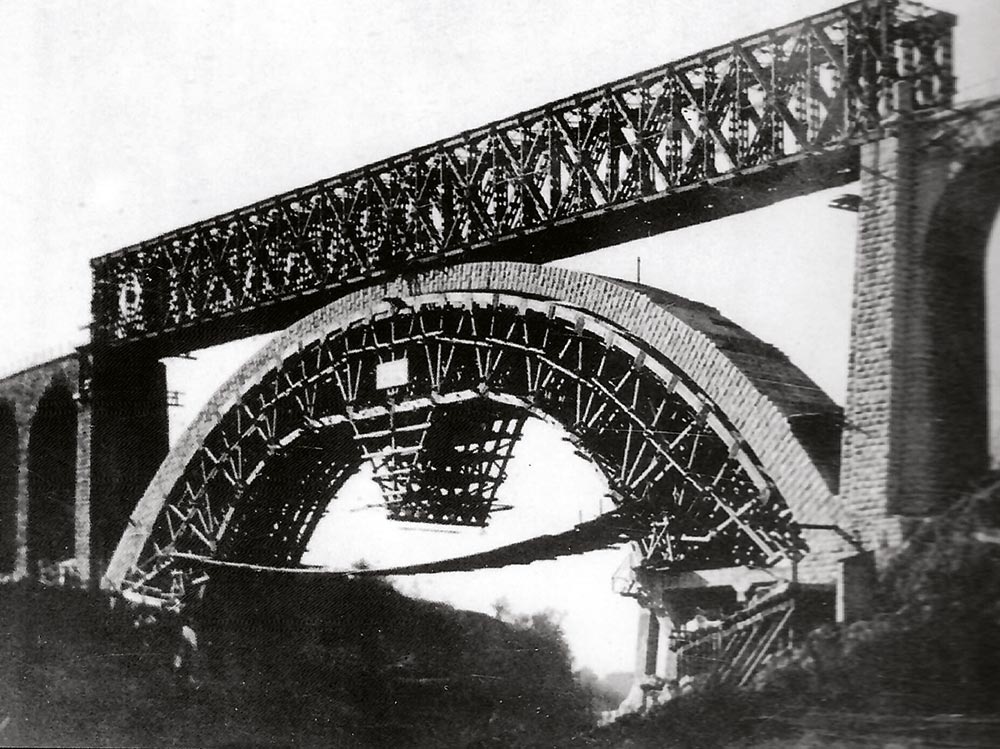

On 19 July 1906, the second railway connection to the port of Trieste was officially inaugurated. Archduke Franz Ferdinand—who would later be assassinated in Sarajevo in 1914—presided over the opening ceremony. The railway’s most challenging section, the Bohinj Railway (also known as Transalpina), ran along the Jesenice-Gorizia route and featured 28 tunnels and multiple bridges. Among these structures stood the Solkan (Salcano) railway bridge, built between 1904 and 1906, which boasted the world’s largest stone arch with an 85-metre span. The bridge achieved worldwide recognition upon completion and still holds its record among stone bridges today.Shortly after its opening, the Transalpina railway line experienced heavy traffic, connecting the prosperous industrial hinterland of Central Europe—Vienna, Southern Bohemia, and Bavaria—with Trieste, a strategic port of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. When World War I broke out and the Isonzo front opened in May 1915, the railway’s role changed dramatically. The war also marked the fate of the Solkan bridge: on the night of 8-9 August 1916, the Austrian engineering units, retreating to the left bank of the Soča-Isonzo, blew up the bridge’s arch, sending it crashing into the river below. Following the breakthrough at Caporetto in October 1917, the Austro-Hungarian forces swiftly regained control of the area, and the Austrian engineers began rebuilding the bridge. Within just two months, by April 1918, they had installed a temporary Roth-Waagner iron lattice structure weighing 650 tons, restoring railway traffic. Though temporary, this technical solution, spanning almost 90 metres, established a record for provisional load-bearing structures—one that remained unmatched throughout the war.

After World War I, most of the Transalpina line, up to the Bohinj tunnel, fell under the Italian State Railways administration, which in 1925 decided to restore the Solkan bridge’s arch. Despite the widespread use of reinforced concrete bridges at the time, the engineering team chose to rebuild the arch in stone to maintain the structure’s historic appearance. The new structure was completed in 1927, while railway traffic continued on the temporary iron lattice structure until its removal, which occurred immediately after the construction of the stone arch was complete. The bridge reopened with a grand ceremony on 8 August 1927. The new arch differed slightly from the original: it was about 40 centimetres narrower and had four openings above each half of the main arch instead of the original five.

World War II also took its toll on the Solkan Bridge. Between 1944 and 1945, the structure was the target of six intense air raids by Anglo-American aircraft. The nighttime attacks, launched from high altitude, caused civilian casualties in Solkan and extensive damage as hundreds of heavy bombs were dropped on the bridge. On 15 March 1945, one of these struck the arch, damaging it but not causing it to collapse into the Soča-Isonzo. Immediately after the war ended, the Allied military administration began restoration work. Through various maintenance and repairs over the years, the bridge has remained essentially unchanged to this day.

Archive: G. Humar

Archive: G. Humar

Archive: G. Humar

Archive: G. Humar

BRIDGE CONSTRUCTION AND STRUCTURAL ENGINEERING

THE CONSTRUCTION OF THE BRIDGE BETWEEN 1904 AND 1906 AUSTRIAN BUILDERS

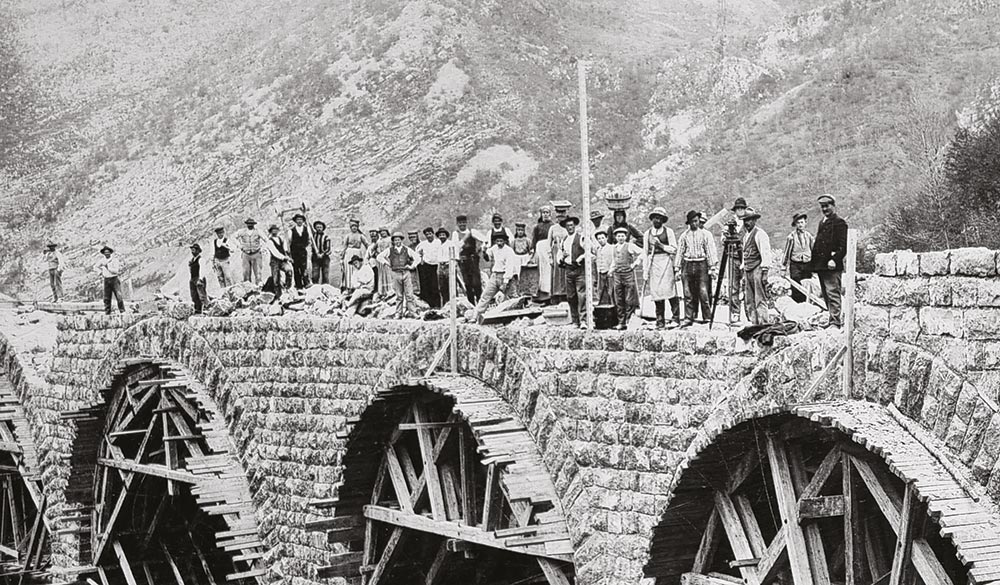

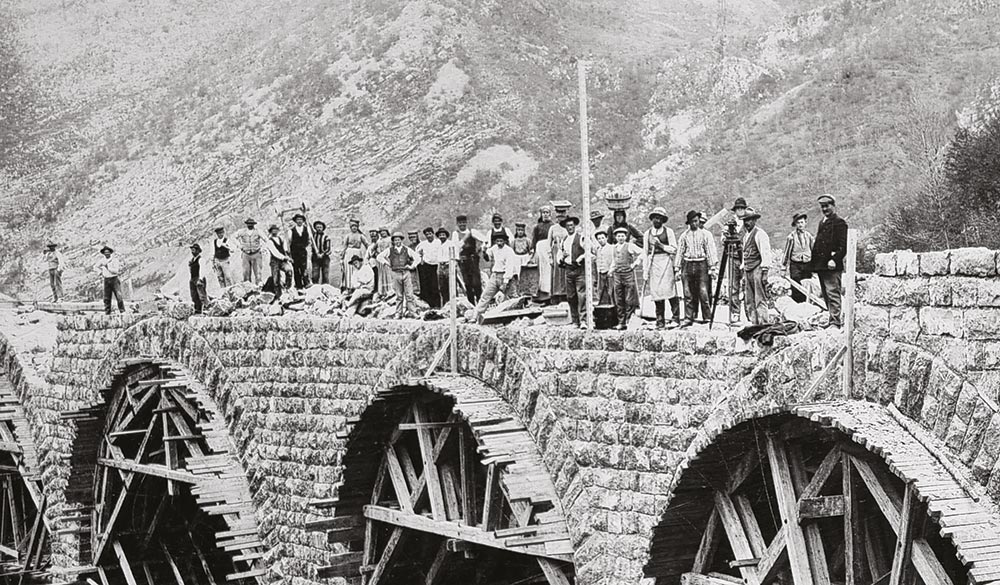

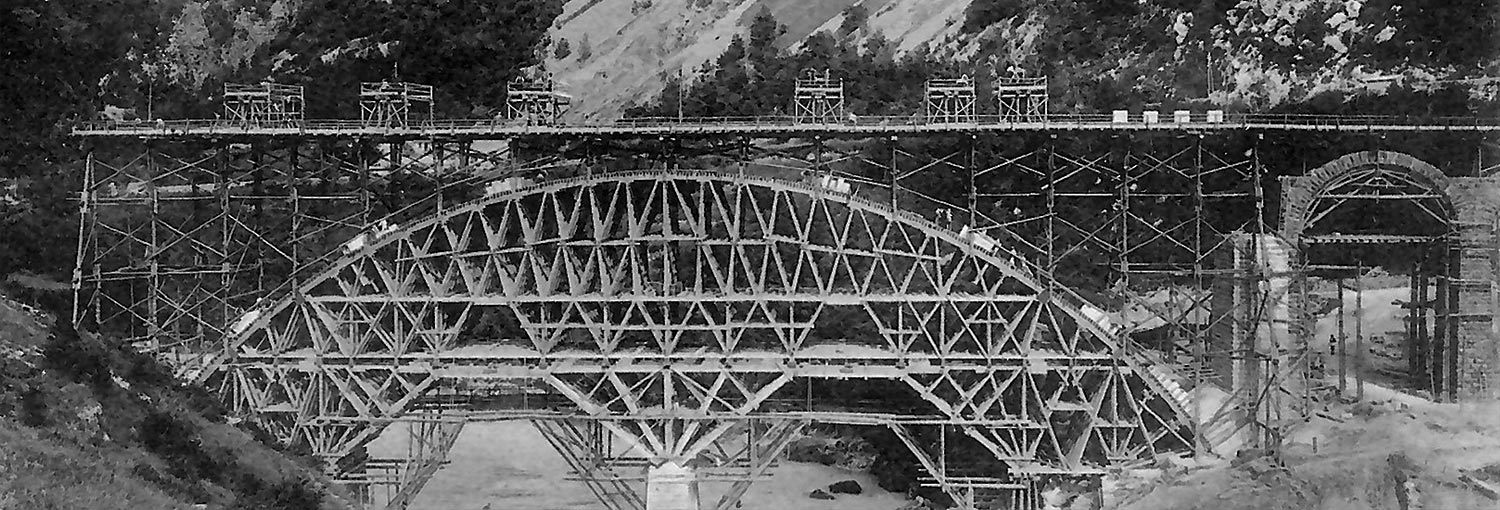

The Austrian engineers designing and building bridges along the Transalpina railway gained extensive experience constructing similar, though smaller, bridges before undertaking the Solkan bridge project. During excavations for the foundations on the Soča-Isonzo’s left bank in the spring of 1904, the team encountered unexpected difficulties that complicated operations. While the original design called for an 80-metre arch span, challenging geological conditions at the left bank foundation site forced designers to extend it to 85 metres. This unplanned modification ultimately earned the Solkan bridge its distinction as the world record holder among stone bridges. This unexpected change in arch size led to the Solkan Bridge achieving the world record among stone bridges.The new bridge was built by the renowned Viennese company Brüder Redlich & Berger under the direction of engineers Rudolf Jaussner and 27-year-old Leopold Örley. The greatest challenge in constructing the central load-bearing element—the stone arch—was creating adequate supporting scaffolding. The most complex task involved installing the fan-shaped support platform, particularly positioning the central support in the riverbed, as due to the Soča-Isonzo’s torrential nature, water levels could rise by up to 8 metres in a mere couple of hours. In just three months, in the spring of 1905, the building team erected a robust supporting scaffolding of premium-quality wood, enabling the installation of the stone arch blocks. A concrete foundation was built using the caisson technique at the riverbed’s centre

The stone voussoirs were transported by rail from the Aurisina quarry to the Gorizia South railway station, then transferred via narrow-gauge railway to the bridge construction site. At the site, the engineering team methodically stored and numbered each piece to indicate its precise installation position. Construction began on 1 June 1905, and the arch was complete in just 18 working days—by 21 June. The project required laying 1,941 m³ of stone voussoirs, totalling over 5,200 tons. Following the established French school of stone bridge construction, the team gradually installed the components in symmetrically balanced arch segments. Advanced geodetic instrumentation monitored the supporting scaffolding’s deformation and settlement patterns throughout construction. When the supporting structure was removed upon completion, the stone arch settled merely 6 millimetres under its own mass.

BRIDGE CONSTRUCTION AND STRUCTURAL ENGINEERING

THE CONSTRUCTION OF THE BRIDGE BETWEEN 1904 AND 1906 AUSTRIAN BUILDERS

The Austrian engineers designing and building bridges along the Transalpina railway gained extensive experience constructing similar, though smaller, bridges before undertaking the Solkan bridge project. During excavations for the foundations on the Soča-Isonzo’s left bank in the spring of 1904, the team encountered unexpected difficulties that complicated operations. While the original design called for an 80-metre arch span, challenging geological conditions at the left bank foundation site forced designers to extend it to 85 metres. This unplanned modification ultimately earned the Solkan bridge its distinction as the world record holder among stone bridges. This unexpected change in arch size led to the Solkan Bridge achieving the world record among stone bridges.The new bridge was built by the renowned Viennese company Brüder Redlich & Berger under the direction of engineers Rudolf Jaussner and 27-year-old Leopold Örley. The greatest challenge in constructing the central load-bearing element—the stone arch—was creating adequate supporting scaffolding. The most complex task involved installing the fan-shaped support platform, particularly positioning the central support in the riverbed, as due to the Soča-Isonzo’s torrential nature, water levels could rise by up to 8 metres in a mere couple of hours. In just three months, in the spring of 1905, the building team erected a robust supporting scaffolding of premium-quality wood, enabling the installation of the stone arch blocks. A concrete foundation was built using the caisson technique at the riverbed’s centre

The stone voussoirs were transported by rail from the Aurisina quarry to the Gorizia South railway station, then transferred via narrow-gauge railway to the bridge construction site. At the site, the engineering team methodically stored and numbered each piece to indicate its precise installation position. Construction began on 1 June 1905, and the arch was complete in just 18 working days—by 21 June. The project required laying 1,941 m³ of stone voussoirs, totalling over 5,200 tons. Following the established French school of stone bridge construction, the team gradually installed the components in symmetrically balanced arch segments. Advanced geodetic instrumentation monitored the supporting scaffolding’s deformation and settlement patterns throughout construction. When the supporting structure was removed upon completion, the stone arch settled merely 6 millimetres under its own mass.

Archive: G. Humar

GLOSSARY

AN EASY-TO-USE REFERENCE TOOL

Bridge, Abutments; Arch; Beams; Bridge length; Centering; Chord; Crossbeam; Deck; Deck span; Expansion joint; Footbridge; Foundations; Hangers; Piers, Pillars, Pylons; Pier cap; Piers; Rise; Roadway width; Span; Stay cables; Structural Bearings; Structural cable; Support; Towers or Pylons; Truss structure; Tie.ARCH RECONSTRUCTION 1925-1927 ITALIAN BUILDERS

The Italian State Railways entrusted construction to Attilio Ing. Ragazzi, a distinguished Milan-based engineering firm. While the initial approach followed the Austrian technical designs, plans had to be adapted when flooding compromised the formwork for the new pier. The engineering team developed an innovative solution: an arch scaffolding system that required no support in the Soča-Isonzo River, avoiding high water level risks. The construction process presented a further technical challenge, as continuous rail traffic on the World War I-era iron load-bearing structure significantly limited the space available for the stone voussoirs. These voussoirs were mainly sourced from the Chiampo quarry near Vicenza, with additional materials from the Aurisina and Aviano quarries. In just over three months, 4,533 numbered stone voussoirs were precisely installed. The joints were sealed by applying Portland cement mortar sourced from the Anhovo cement factory.A new cast iron railing was installed along the newly constructed section above the arch. From an architectural perspective, the stone voussoirs of the new (Italian) arch feature subtle variations in shape and structure that enhance its elegance. The distinctive arch remains a defining feature of the Solkan Bridge, preserved in its authentic configuration to this day.

Photo by: K. Brešan

THE SOLKAN BRIDGE TODAY

The Solkan Bridge maintains its reputation as having the world’s largest stone arch. Although China did build stone-arch structures spanning 145 metres in the late 20th century, these projects traversed arid valleys. The Solkan Bridge, by contrast, presented the additional engineering challenge of requiring arch support during construction over an active waterway.In 1996, civil engineer Gorazd Humar published a detailed monograph titled Kamniti velikan na Soči (The Stone Giant on the Soča). Following extensive research in Viennese and Italian archives, he thoroughly documented the bridge’s initial construction (1904–1906) and subsequent reconstruction efforts (1925–1927). Through his comparison with similar European bridges, Humar has confirmed the Solkan Bridge’s rightful status as the foremost structure of its kind. The Austrian designers gave the bridge a striking Art Nouveau character reflected in its architecture. The crown jewel was an ornate cast-iron railing decorated with stylised laurel wreaths installed above the arch—a characteristic design element of the era. This signature feature was originally designed for Vienna’s urban railway by Otto Wagner, master of Viennese Art Nouveau, possibly in collaboration with the distinguished Slovenian architect Jože Plečnik. The ornamental railing ran along the bridge above the main arch, ending on both sides with distinctive Art Nouveau stone posts. As the only bridge outside Vienna to feature this Wagnerian design, the Solkan Bridge received the imperial seal. It was the only bridge outside Vienna adorned with this distinctive railing—a detail that highlighted its extraordinary historical importance.

When the arch collapsed in 1916, the entire Wagner railing plunged into the depths of the Soča-Isonzo River. In 1999, divers made a remarkable discovery, recovering sections of the railing—though their origin was a mystery at the time. The puzzle was finally solved in 2022 when analysis of the architectural fragments confirmed their Viennese origin. These recovered artefacts are now on display at the Goriški Muzej museum in Nova Gorica. Having earned recognition as a monument of local importance in 1985, the Solkan railway bridge now awaits its elevation to national monument status. The surrounding area has evolved into a venue for remarkable events—hosting its first wedding ceremony in 2021, while in 2019, aerobatic pilot Benjamin Ličer completed his third daring flight beneath the bridge’s majestic arch.

The Solkan Bridge stands as a distinguished landmark of both the Gorica region and Slovenia, commanding respect on the international stage. Beyond its technical excellence, it is a testament to successful cultural collaboration. Through its development—encompassing both Austrian construction and Italian renovation phases—the bridge showcases exceptional engineering from multiple traditions. For example, Italian contractors built the current architectural features between 1925 and 1927, employing advanced stone-working techniques that trace their lineage to Venice’s iconic Rialto Bridge. This remarkable structure exemplifies engineering sophistication through its seamless blend of Austrian, Italian, French, and Slovenian design and construction methods.