mainizza

Mainizza Roman Bridge

Michele ZOFF

Associazione Culturale Lacus Timavi - Monfalcone

Associazione Culturale Lacus Timavi - Monfalcone

HISTORY

A ROMAN ROAD IN THE HEART OF EUROPE

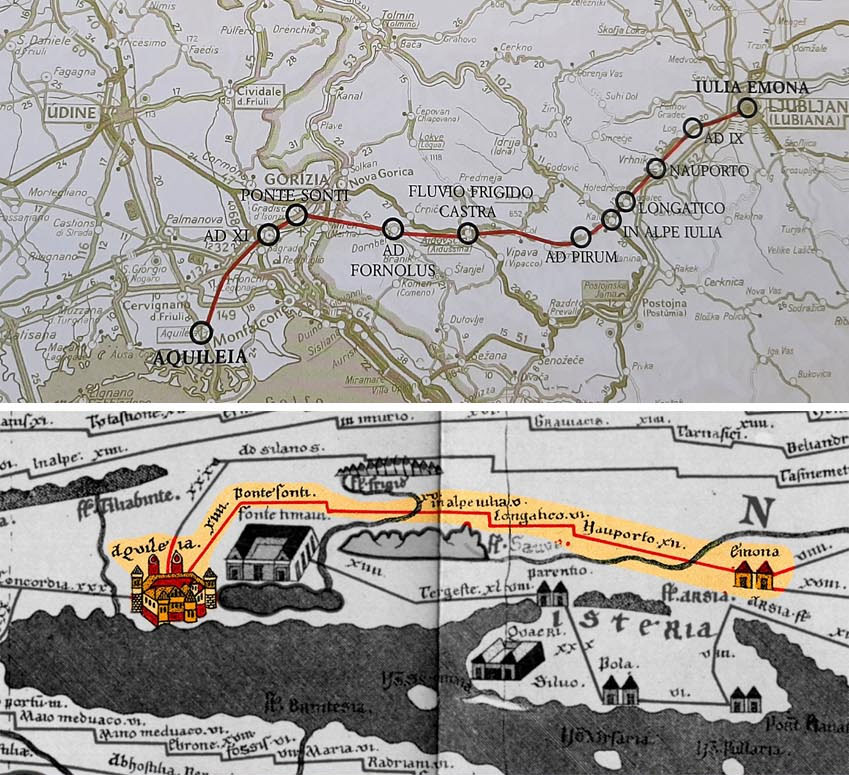

In Roman times, a road traversed the territory of Farra d’Isonzo, part of the Aquileian countryside, connecting Aquileia to the Danubian region (Pannonia). This 114-kilometre route appears in ancient itinerary guides: the Itinerarium Antonini, the Itinerarium Burdigalense, and the Tabula Peutingeriana—a medieval map of the Roman Empire’s military roads. Beginning in Aquileia, the road curved northeast through Gradisca d’Isonzo, crossed the Isonzo at Pons Sontii (Mainizza di Farra d’Isonzo) and followed the Vipava Valley to Fluvius Frigidus (Ajdovščina). The route then ascended to the Piro Pass at 867 metres, descended toward Longaticum, and proceeded to Nauportus (Vrhnika) before reaching Emona (Ljubljana). This gravel-paved road witnessed the passage of historical figures like Octavian Augustus and, during the Empire’s decline, served as a path for “barbarian” peoples advancing toward Italy.THE BRIDGE OVER THE AESONTIUS RIVER, AN EXAMPLE OF ANCIENT ENGINEERING

About twenty-one kilometres from Aquileia, the gravel road connecting the city to Emona (Ljubljana) crossed the Isonzo River near Mainizza, close to today’s Church of the Sacred Heart of Mary. At this location, known in historical sources as Pons Sontii, stood a bridge and a mansio (rest station) alongside a sacred area and a monumental necropolis. During low water periods in the 1600s, the remains of the structure were still visible. Research began in the 1900s to develop reconstruction theories based on ancient sources. These studies uncovered elevation blocks that had been repurposed from the nearby monumental necropolis, which had been active two centuries earlier. This finding suggested the bridge was likely rebuilt in the 3rd century AD.THE INSCRIPTIONS ON THE ANCIENT FUNERARY MONUMENTS

The end of the ancient world was marked by declining literacy—the level achieved in the Roman Empire by the early 6th century AD wouldn’t be matched in Europe until the 1800s.During the early Middle Ages and beyond, very few could decipher the Latin inscriptions in burial grounds arranged along the roads outside the city. Each tomb occupied its own defined space, enclosed by low walls, fences, or hedges. The main monument stood within, while the funerary enclosures facing the road were arranged in rows. Wealthy families had prominent positions at the front, alongside the affluent freed slaves (liberti). The inscriptions began with the deceased’s three names (tria nomina), indicating whether they were freeborn (ingenuus) or freedmen. They sometimes named family members, friends, and the monument’s builder. The epitaphs occasionally included testamentary provisions, detailing bequests for the tomb’s upkeep and commemorative ceremonies.

HISTORICAL FIGURES WHO CROSSED THE BRIDGE

This bridge, fundamental to the Roman road system, witnessed the passage of numerous armies and historical figures. In AD 238, the historian Herodian records that Maximinus Thrax—the first emperor of barbarian origin—found the bridge destroyed by the people of Aquileia. He constructed a makeshift bridge of barrels to cross the Isonzo, only to be killed by his own soldiers in Aquileia. In AD 394, Flavius Eugenius crossed the bridge to confront Theodosius I in the Battle of the Frigidus, a conflict that marked Christianity’s triumph in the Roman Empire. In AD 401, Alaric led his Visigoths across to invade Italy, while in AD 452, Attila traversed it during his campaign, which culminated in Aquileia’s destruction. In AD 489, Theodoric, commanding his formidable cavalry, defeated Odoacer near the bridge. The final significant crossing came in AD 568 when the Longobards, under Alboin’s leadership, passed over en-route to Forum Julii (Cividale), where he established his duchy’s capital and appointed his nephew Gisulf I governor.

BRIDGE CONSTRUCTION AND STRUCTURAL ENGINEERING

GEOMORPHOLOGY OF THE AREA WHERE THE BRIDGE WAS BUILT

Roman bridges are rightfully considered masterpieces of engineering and, in many cases, bear witness to the existence of ancient road routes that have vanished over time. The earliest structures were made of wood, allowing them to be dismantled and reassembled. By the late 2nd century BC, masonry bridges—featuring arches supported by piers—became the prevalent design.Construction proved challenging, especially in turbulent waters. In De architectura (1st century BC), Vitruvius describes the technique of building a watertight caisson using piles and clay to create a dry chamber where the piers could be built. To prevent erosion, engineers sometimes placed the piers outside the riverbed. They constructed stone arches using wooden supporting frameworks, carefully laying precisely cut blocks up to the keystone. These structures could achieve spans exceeding 30 metres, while innovative drainage features—small archways integrated into the piers—were incorporated to manage water flow during flood conditions.

THE ART OF BRIDGE BUILDING IN THE ROMAN ERA

The Isonzo River is about 136 kilometres long: it originates in the Trenta Valley in Slovenia and flows into the Adriatic Sea near Monfalcone. The river’s torrential flow features striking emerald waters that gather tributaries from the southern slopes of the Julian Alps.Near Gorizia, limestone formations in the northern catchment basin transition into low-permeability marly-arenaceous rocks, forming the Collio hills. Quaternary alluvial deposits extend to the river’s confluence with the Vipacco River. Beyond this point, the river basin is characterised by the Carso plateau and, along its right bank, the alluvial fans of the Isonzo and Torre rivers. Between Gorizia and Pieris, where the Roman bridge stands, the riverbed cuts through highly permeable gravelly alluvium—a section that often runs nearly dry during low-flow periods.

INVESTIGATION INTO THE MAINIZZA BRIDGE REMAINS

In 2012, ArcheoTest Srl conducted an investigation in the Isonzo riverbed on behalf of the Superintendency for Architectural and Landscape Heritage of Friuli Venezia Giulia, comprising four exploratory surveys. The first survey examined seemingly interconnected stone blocks near the bank of Villanova di Farra (Mainizza locality). The second survey, conducted in the river’s centre, focused on scattered, unconnected blocks. The third survey identified a bridge pier on the left bank, while the fourth revealed a similar pier—aligned with the Roman road discovered in Savogna d’Isonzo. Analysis of the first survey’s findings, considering the structure’s overall layout, showed that the blocks served as bank reinforcement rather than a bridge pier, evidenced by the absence of binding materials and metal clamp holes. The limestone blocks found in the second survey likely belonged to the bridge’s upper section from a reconstruction phase. The third and fourth surveys were performed on the area where the previously discovered Roman road would have extended.CONSTRUCTIVE EVIDENCE AND HYPOTHESES ON THE NATURE OF THE ROMAN BRIDGE

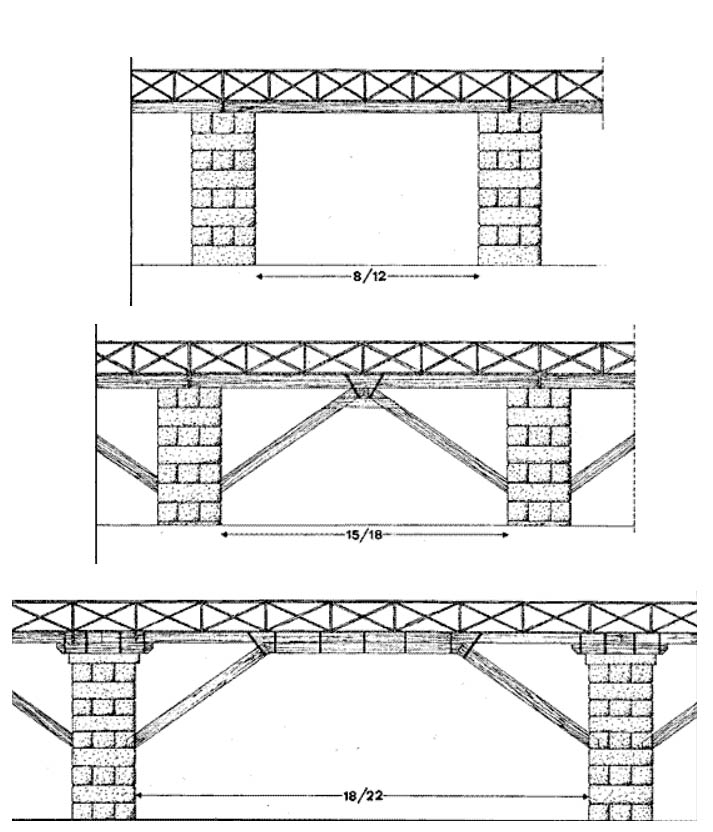

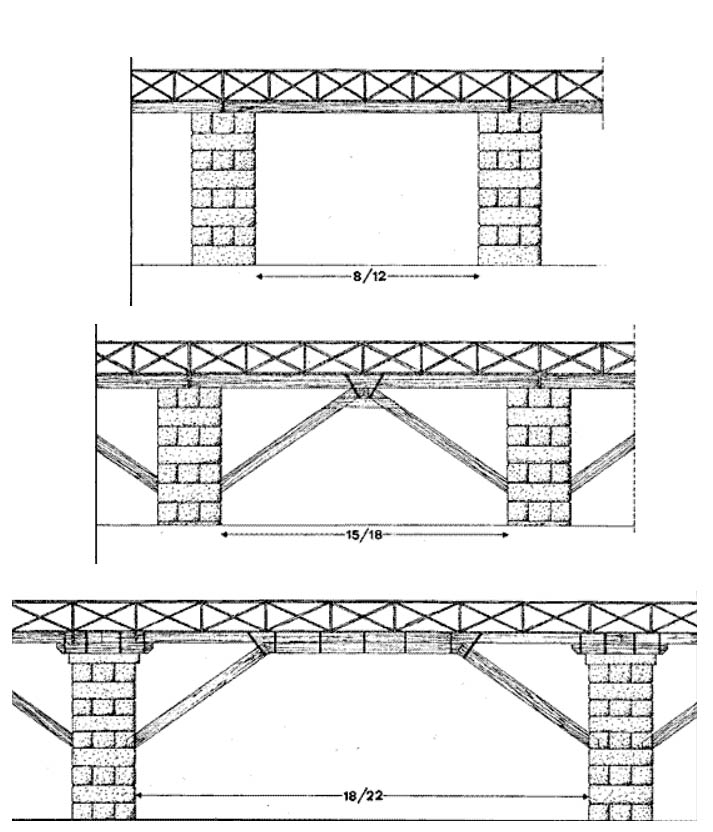

The third and fourth surveys uncovered the bases of two rectangular bridge piers (9 x 4.5 metres) with longer sides aligned with the river’s current. Archaeologists found a system of oak piles reinforced by blocks in the riverbed that protected the pier base and reduced water impact. The base, constructed of rectangular sandstone blocks, contains holes for iron and molten lead insertions. The fourth survey revealed a foundation layer where blocks were missing, consisting of sandstone fragments, hydraulic cement, and wood pieces. The varying dimensions of the piers suggest that the bridge featured decreasing arches in a mixed construction style, with stone vertical supports combined with wooden horizontal elements. The lack of bricks and trapezoidal stones indicates the bridge used wooden load-bearing beams rather than brick arches. Breakwaters were used instead of traditional cutwaters to manage strong currents.BRIDGE CONSTRUCTION AND STRUCTURAL ENGINEERING

GEOMORPHOLOGY OF THE AREA WHERE THE BRIDGE WAS BUILT

Roman bridges are rightfully considered masterpieces of engineering and, in many cases, bear witness to the existence of ancient road routes that have vanished over time. The earliest structures were made of wood, allowing them to be dismantled and reassembled. By the late 2nd century BC, masonry bridges—featuring arches supported by piers—became the prevalent design.Construction proved challenging, especially in turbulent waters. In De architectura (1st century BC), Vitruvius describes the technique of building a watertight caisson using piles and clay to create a dry chamber where the piers could be built. To prevent erosion, engineers sometimes placed the piers outside the riverbed. They constructed stone arches using wooden supporting frameworks, carefully laying precisely cut blocks up to the keystone. These structures could achieve spans exceeding 30 metres, while innovative drainage features—small archways integrated into the piers—were incorporated to manage water flow during flood conditions.

THE ART OF BRIDGE BUILDING IN THE ROMAN ERA

The Isonzo River is about 136 kilometres long: it originates in the Trenta Valley in Slovenia and flows into the Adriatic Sea near Monfalcone. The river’s torrential flow features striking emerald waters that gather tributaries from the southern slopes of the Julian Alps.Near Gorizia, limestone formations in the northern catchment basin transition into low-permeability marly-arenaceous rocks, forming the Collio hills. Quaternary alluvial deposits extend to the river’s confluence with the Vipacco River. Beyond this point, the river basin is characterised by the Carso plateau and, along its right bank, the alluvial fans of the Isonzo and Torre rivers. Between Gorizia and Pieris, where the Roman bridge stands, the riverbed cuts through highly permeable gravelly alluvium—a section that often runs nearly dry during low-flow periods.

INVESTIGATION INTO THE MAINIZZA BRIDGE REMAINS

In 2012, ArcheoTest Srl conducted an investigation in the Isonzo riverbed on behalf of the Superintendency for Architectural and Landscape Heritage of Friuli Venezia Giulia, comprising four exploratory surveys. The first survey examined seemingly interconnected stone blocks near the bank of Villanova di Farra (Mainizza locality). The second survey, conducted in the river’s centre, focused on scattered, unconnected blocks. The third survey identified a bridge pier on the left bank, while the fourth revealed a similar pier—aligned with the Roman road discovered in Savogna d’Isonzo. Analysis of the first survey’s findings, considering the structure’s overall layout, showed that the blocks served as bank reinforcement rather than a bridge pier, evidenced by the absence of binding materials and metal clamp holes. The limestone blocks found in the second survey likely belonged to the bridge’s upper section from a reconstruction phase. The third and fourth surveys were performed on the area where the previously discovered Roman road would have extended.CONSTRUCTIVE EVIDENCE AND HYPOTHESES ON THE NATURE OF THE ROMAN BRIDGE

The third and fourth surveys uncovered the bases of two rectangular bridge piers (9 x 4.5 metres) with longer sides aligned with the river’s current. Archaeologists found a system of oak piles reinforced by blocks in the riverbed that protected the pier base and reduced water impact. The base, constructed of rectangular sandstone blocks, contains holes for iron and molten lead insertions. The fourth survey revealed a foundation layer where blocks were missing, consisting of sandstone fragments, hydraulic cement, and wood pieces. The varying dimensions of the piers suggest that the bridge featured decreasing arches in a mixed construction style, with stone vertical supports combined with wooden horizontal elements. The lack of bricks and trapezoidal stones indicates the bridge used wooden load-bearing beams rather than brick arches. Breakwaters were used instead of traditional cutwaters to manage strong currents.