Bridges and wars

Wars,

all wars

destroy

bridges

Bridges are considered strategic military targets because they enable the passage of people and goods—and, with them, the flow of ideas, experiences, and knowledge.

Throughout history, the bridges over the Isonzo-Soča River have been destroyed and rebuilt countless times.

The land our river flows through is a significant border region that has been shaped by waves of diverse populations and governing entities over time.

Many bridges in our territory still bear the scars of war, particularly those of the devastating conflicts of the twentieth century. These structures tell not only their own history but also that of the river and surrounding landscape.

The curated collection of photographs presented here captures these compelling stories. Though simple, this visual narrative speaks volumes.

These images compel us to contemplate war’s tragedy—its destructive force that compromises both the physical integrity of bridges and their symbolic role in uniting territories and peoples.

NO MORE PAIN

AND DESTRUCTION,

BUT ONLY ACTIONS THAT LEAD

TO DEVELOPMENT

AND THE WELL-BEING

OF POPULATIONS.

IN ITS CURRENT

LIKE ONE OF ITS OWN STONES

I HOISTED MYSELF

UP AND WENT

LIKE AN ACROBAT

OVER THE WATER

I SQUATTED DOWN

NEAR MY CLOTHES

FOUL WITH WAR

AND LIKE A BEDOUIN

BOWED DOWN TO RECEIVE

THE SUN

THIS IS THE ISONZO

AND HERE I HAVE

BEST KNOWN MYSELF TO BE

AN OBEDIENT NERVE

OF THE UNIVERSE

From “Rivers” by Giuseppe Ungaretti,

written in Cotici on 16 August 1916

Translated by Patrick Creagh (1930 – 2012)

THE BRIDGES ON THE ISONZO-SOČA RIVER DURING WARTIME

Bridges of all kinds have always been the first casualties of war. The Isonzo-Soča River basin—situated at a crucial crossing point between the Apennine peninsula and Eastern Europe—has facilitated the movement of countless armies throughout history. During the Roman period, one of the grandest Roman bridges stood near Mainizza, south of Gorizia—spanning the Isonzo-Soča, of which only a few foundational elements are still visible today. Whether this bridge succumbed to warfare or the river’s rising waters over the centuries remains unknown. Early chronicles tell us that the Venetians demolished the bridge over the Isonzo-Soča near Caporetto (Kobarid) to halt invading forces. During the French occupation of the region (1809–1813), Napoleon’s forces destroyed this same bridge, which had been rebuilt only decades before

WARS ARE AN EVIL,

EVEN FOR BRIDGES

Gorazd Humar

THE BRIDGES ON THE ISONZO-SOČA RIVER DURING WORLD WAR I

The bridges along the Isonzo-Soča River faced their most dramatic challenges during World War I when, on 24 May 1915, the Italian army attacked the Austro-Hungarian forces defending positions along the river. Almost all major bridges sustained extensive damage during the twelve Battles of the Isonzo. The Napoleon Bridge, formerly known as the Caporetto Bridge, became the first casualty merely 48 hours into the conflict.

The bridges were destroyed both during combat and by the retreating armies on both banks of the Isonzo-Soča River.

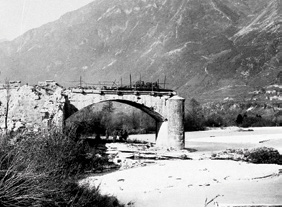

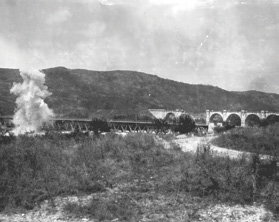

During the Third Battle of the Isonzo in October 1915, the central stone sections of the three arches of the railway bridge near Aiba (Ajba), not far from Canale (Kanal), were blown up. The Austro-Hungarian engineering units carefully planned this demolition during their tactical retreat, knowing they could later rebuild the collapsed section with a prefabricated Roth-Waagner-type iron bridge if needed. This opportunity came after the military situation shifted following the turning point at Caporetto in October 1917, and railway traffic resumed within a month. The same fate befell the famous Salcano (Solkan) railway bridge, which boasts the world’s largest stone arch with an 85-metre span.

Other bridges along the river in the Gorizia sector were also destroyed in this battle. Following the breakthrough of the Isonzo front at Caporetto in the spring of 1918, Austro-Hungarian troops erected a temporary Roth-Waagner-type iron bridge across the damaged section, successfully restoring railway operations within approximately one month.

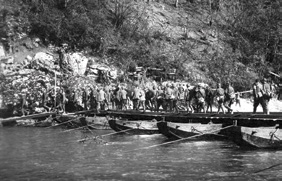

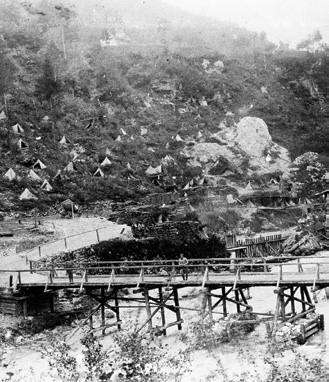

Throughout World War I, numerous emergency wooden and pontoon bridges were constructed along the Isonzo-Soča River to support military operations on both banks.

The Italian forces alone implemented 14 pontoon bridges in the stretch between Plava (Plave) and Doblar during the Tenth and Eleventh Battles of the Isonzo in 1917—all of which became vulnerable targets for enemy attacks. Notable wooden structures included the Caporetto bridge, constructed by the Italian army in the early stages of the hostilities, and the large wooden bridge near Tolmino (Tolmin), which stood beside the damaged stone bridge.

THE BRIDGES ON THE ISONZO-SOČA RIVER DURING WORLD WAR II

During World War II, the bridges over the Isonzo-Soča suffered severe damage. In 1944, Anglo-American air forces intensified their attacks on the region’s main infrastructure, particularly targeting railway bridges. The Salcano railway bridge withstood multiple aerial assaults, though these unfortunately resulted in civilian losses. During one attack in March 1945, a bomb damaged the bridge’s arch—which had been restored in 1927—though structural integrity remained largely intact. The large stone railway bridge at Aiba, near Canale, met a different fate: in February 1945, it was almost completely destroyed. Subsequently, a modern reinforced concrete structure was erected in its place in 1954.

THAT MAN ERECTS

AND BUILDS IN HIS URGE

OF LIVING,

NOTHING IS, IN MY EYES,

BETTER AND MORE

VALUABLE THAN BRIDGES.

THEY ARE MORE IMPORTANT

THAN HOUSES,

MORE SACRED THAN SHRINES

AND THEY DO NOT SERVE

FOR ANYTHING SECRET

OR BAD.

Nobel Prize for Literature in 1961